Sir Bradley Wiggins smashed the Hour Record with 54.526 km

The hour record was smashed on the 7th of June 2015. Through the heat and humidity of the climate controlled stadium, the roar of 6000 spectators, and to the steady beat of The Chemical Brothers -now synonymous with the incredible atmosphere of London’s temple to cycling- Britain’s most renowned cyclist, Sir Bradley Wiggins, attempted his final, greatest cycling challenge. The hour record.

Once among the greatest and most prestigious prizes in cycling, the hour record has languished in relative obscurity outside of the cycling community, with little wider interest and few attempts since the mid nineties. With the goal to ride as far as physically possible on a banked track in one hour, aerodynamics quickly became the prime limiting factor for record attempts. With disagreement over what constitutes a level playing field, and subsequent rule changes which have left previous records moot -including Chris Boardman’s incredible 56.375 kilometres riding in the ‘superman’ position- there has been little appetite for the competition. That is, until the winter of last year.

With the UCI’s decision to clarify the design requirements for ‘legal’ bicycles, they have reinvigorated the competition, restoring its reputation as track cycling’s ultimate test of speed and endurance. Friend of Yellow Jersey, Jens Voigt, was the first to set a ‘new’ record, covering 51.110km in his farewell to professional cycling last June. Small gains on the record were made by Matthias Brändle and Rohan Dennis, with Alex Dowsett’s attempt at the Manchester Velodrome last month making him the rider to beat with a distance of 52.937km.

Arguably, the hour record hasn’t been so hotly contended, nor so regularly challenged since the battle between pioneers Oscar Egg and Marcel Berthet, more than 100 years ago. The back and forth battle for the hour record took place between 1907 and 1914, in which time the ‘Vélodrome Buffalo’ became the competition’s home, hosting each of Egg and Berthet’s hour record rides. Built in Paris in 1893, the track took its name from Buffalo Bill Cody, who had performed on the grounds with his circus. Its director for the period, Tristan Bernard, is widely credited for introducing the final lap bell to track events.

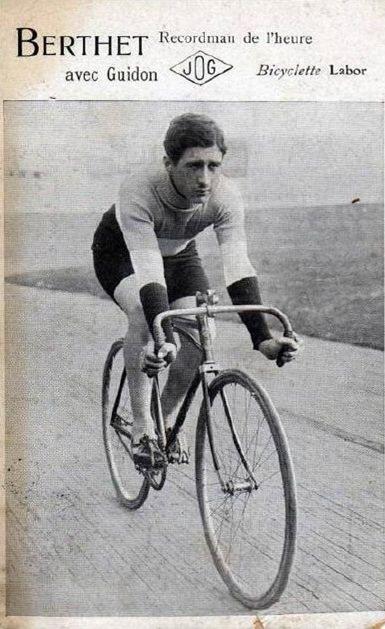

For five years from 1907, Frenchman Marcel Berthet had held the hour record at 41.520km. There are various quotes attributed to Marcel from after his ride, but they all follow the same theme, reminiscent of what we hear from modern competitors- never again. Despite languishing for half a decade, the record caught the attention of twenty two year old Swiss road rider Oscar Egg.

Allegedly uninterested in cycling until watching the 1909 Paris-Roubaix pass aged 19, Oscar was struck by the bug, giving up his studies in Industrial Design in Paris to pursue cycling as a profession. Three years later he was ready to challenge Marcel Berthet’s record, breaking it by 840 meters on wooden rims and a 24 by 7 gear ratio. A re-measure of the Buffalo track a year later showed their count had been off by 1.7 meters per lap, raising his achievement to 42.360 kilometres.

Despite Marcel Berthet’s insistence that once was enough, he was back on the track in August of 1913 for a new attempt. This time using precise lap timings to inform his pace; Berthet claimed he would pull out of the race if he were to lag more than 50 meters behind Egg’s pace, and it is thought that this is the first example of a track cyclist using lap timings to measure his progress and effort in this way. Berthet was able to win back the record with a ride of 42.741 kilometres, however Oscar Egg was present in the crowd as a spectator, and waited just two weeks before adding another 784 meters to the record.

An early innovator in cycling, Berthet left nothing to chance for his next attempt the following month. Up until this point the bicycles ridden by the two men were standard of the time, but understanding the role of technology, Marcel Berthet ensured he could give himself the edge. His bicycle was build from specially made, lighter steel tubing. The front forks were straightened to improve aerodynamics, the wooden rims of his wheels planed down until they were paper thin, and (by the standards of the time) super light tires imported from Milan, saving a further 15 grams on weight.

Marcel Berthet on the track

There is no record of what Berthet was wearing for his ride, but he has been named as one of the first in cycling to shave his legs and wear fitted ‘skin suits’ rather than a conventional cotton shirt. In all, Berthet’s efforts added a further 250 meters to the record, but less than a year later on the 18th of June 1914, Egg was back to raise the distance a further 472 meters to 44.247 kilometres.

We will never know if Berthet could have found a way to take the record back for a fourth time. A month later the First World War broke out, and the Vélodrome Buffalo was raised to free up land for an aircraft factory. It is widely suggested that both riders aimed not to beat the other by too much, so as to maintain the stadium filling popularity of their rivalry. Whether fair or not, between them Berthet and Egg raised the hour distance record by almost three kilometres on bicycles made from steel and wood, and Oscar Egg’s record distance stood unbeaten for nearly twenty years.

Since the new, ‘unified hour’ has been introduced by the UCI, and Wiggins announced that he was making an attempt, the hour has returned to the heights it once enjoyed. All 6000 tickets for Bradley Wiggin’s hour sold out in under 7 minutes, and his target to beat is 52.491 kilometres, a full 8244 meters over Oscar Egg’s 1914 best. It seems however that the goal of the riders has shifted somewhat from how it used to be. While Berthet and Egg built their cycling careers around the popularity of the event, Wiggin’s and Voigt seem to have approached the challenge as a farewell.

If Berthet and Egg set distances they knew one another could beat, Bradley Wiggin’s certainly will not. Speaking to The Times, Wiggins said:

“It sounds a bit horrible to say, but I think I could break the record tomorrow […] But I don’t just want to break it, I want to put it right up there, as far out of reach as I can,

“I’ve got 55km in my head and I believe that’s realistic,” “And I think if I do that it will stand for 20 years.”