Power meters have been a feature of professional and amateur cycling since the late 1980s. Team Strawberry first used a Power Pacer prototype in the 1989 Race Across America as part of a wider set of experiments on the human body and its performance. Whilst the team only lasted two years, the prevalence of power meters increases year on year.

The early models used strain gauges, connected to a bar-mounted computer through a network of flimsy external wires. The technology was expensive. The bikes were unsightly and difficult to clean.

Over the past decade, wireless tech has introduced several competitors into the power meter space, with a variety of device types: strain gauges in the cranks, rear hubs and bottom brackets; pressure monitors in the pedals; and opposing force meters calculated from gravity, acceleration, wind speed and frictional drag.

Given the cost of power meters in the early years, they were often the privilege of pros or serious amateurs. Today, however, there are many options to suit most price points. We’re not here to give you a product review or advise on which one you should buy, but we can give you our thoughts on using power, as well as those of some experts and pros.

TOM MCMORRIN – YELLOW JERSEY

Following a couple of collarbone breaks in early 2018, I started using indoor trainers for rehab through our partners Athlete Lab. The primary metric is watts, fluctuating around FTP for the class, depending on the session type.

Never having ridden with power previously, it was interesting to see how my average power output varied considerably based on fatigue, time of day (I found early mornings were consistently lower), what I was doing the night before and even if I had an espresso.

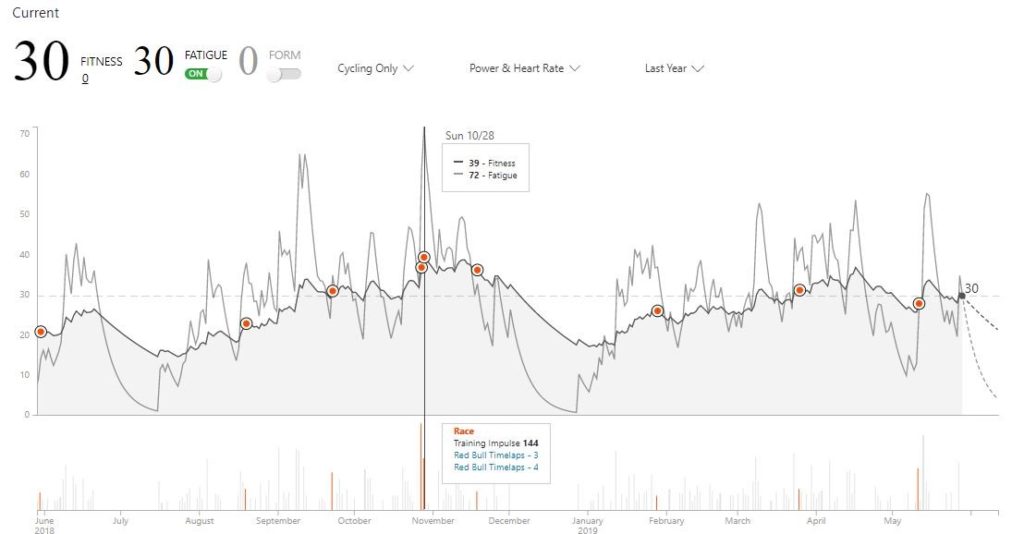

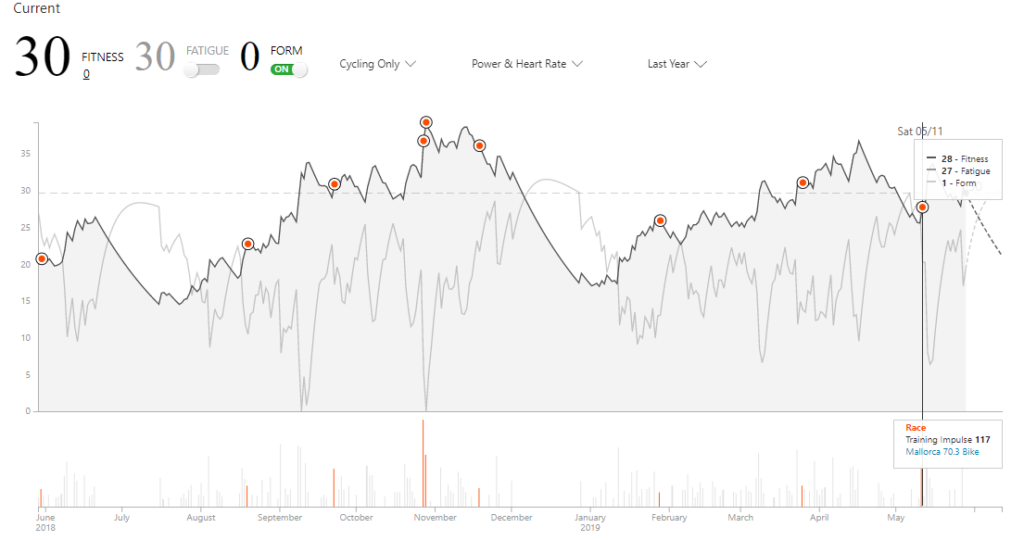

When combining watts with heart rate data, it was an excellent way of gauging form and fatigue. My fatigue unsurprisingly peaked after Red Bull Timelaps, then bottomed out in my festively inactive period.

Indoors, I found I could hold more power than others (I’m 6’5″ and 95kg), but out on the road, factoring in w/kg and wind resistance, they’d drop me in a convincing fashion. I was curious to test a power meter outside to see how indoor power data matched the real thing.

Testing Avio’s crank-based meter

Our new partners at Avio offered to let me test their PowerSense crank-based meter (above). You send off your left crank; they fit and send it back to you – all within the week; I didn’t miss a weekend. You can install it yourself, but it’s advised to get it factory-fitted.

The gauge is sleek, and you wouldn’t notice it unless you hunt for it, nestled between the crank arm and the chain stay. As Avio calibrate the gauge for you in the factory, you just pair it with you computer, then calibrate it within seconds at the start of each ride.

As a novice to ‘outdoor’ power, my immediate observation was how much power on the road would fluctuate from 25% of your FTP up to over 200% purely based on my position in a bunch. Or how a simple 1-minute low-gradient lump would spike my power when I otherwise might not have noticed.

As you would expect, the power readings with the Avio are instant, but heart rate takes a long longer to catch up. Having used power in a controlled environment, I found the data’s variability for measuring effort fascinating.

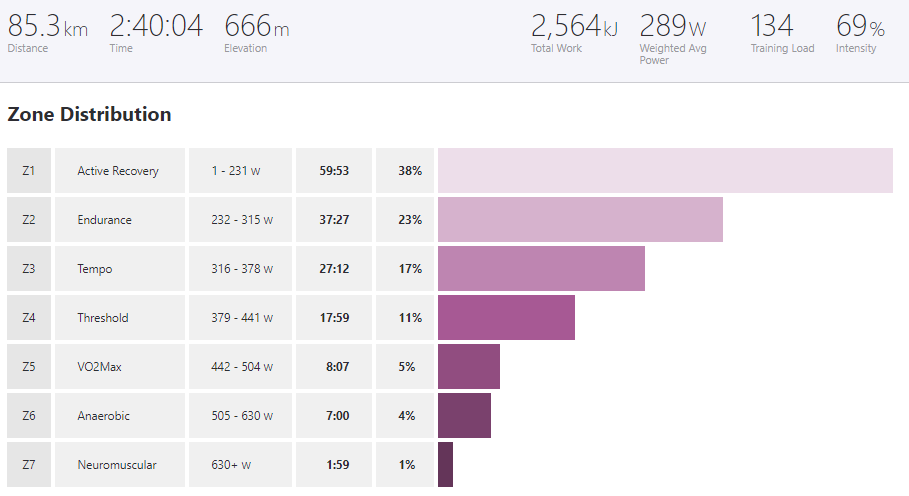

Below is the output from a recent ride with two friends. Despite it feeling pretty hard, an hour of it was very light, without much at the top end either.

On the roads

On British roads, the road surface, wind and junctions impact your average speed and data outputs. I found it easiest to test the power meter on long and steady climbs, where the power would stay constant for 20 minutes plus.

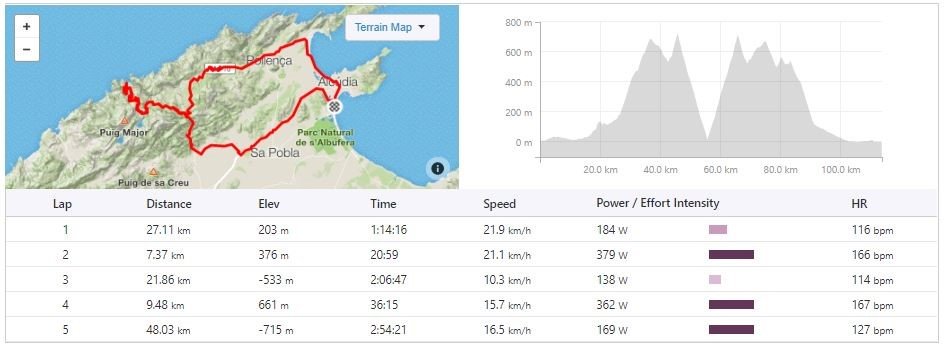

A few weeks ago, I went to Mallorca and gave it some beans up Sa Batalla and Sa Calobra (laps 2 and 4 respectively below).

Once a firm advocate of riding on’feel’ or heart rate, I’m now convinced power data is a far superior metric for gauging effort. At points, you think ‘F*** me this is hard!” Then you look down and you’re churning 650+ watts.

In the past, I might have blindly plugged on and then limped over the final few kilometres, wondering where it all went wrong. Having the power reading staring at me meant I could gauge the effort throughout.

Crunching the numbers

Using data mid-ride is one thing, but I, like many others, enjoy the post-ride analysis. I use Strava premium, but there are many other (potentially better) apps and software available. This, primarily coffee-based, past time is dramatically enhanced when watts are added to the mix.

Interestingly, my form had been dropping consistently for the weeks before the Mallorca Half Ironman earlier this month. This was probably an indicator of things to come as the race turned out to be a pretty awful day out.

Verdict

In the past, I wrote off using power as a perk for the pros or the obsessive. However, with reliable power meters (such as Avio) priced around the £200 mark, the cost vs reward has shifted hugely. For anyone interested in improving their performance on the bike, and monitoring their form, I’d say it’s an essential bit of kit that won’t break the bank.

TOM SHANNEY – HEAD COACH – ATHLETE LAB

Once you have managed to conquer a consistent level of training frequency and duration, the emphasis shifts toward training intensity and structure. This is when adding technology and training aids can be extremely effective.

A power meter is a great addition for those looking to develop structure in their workouts. You will be able to use the data to formulate a training plan specific to your needs and events.

In the zone

All workouts can be based around precise power zones or FTP percentages, developing certain areas of fitness. Although training to heart rate alone is useful, a heart rate monitor only tells you how great the effort is as a measure of input. There is no data to show what output you’re achieving. This is where training with a power meter provides reliable output measurement.

The output data received from indoor training sessions or outdoor riding can be used to shape future structure, highlighting any areas of weakness, need for recovery and guiding your training effectively.

A further benefit of using a power meter is that it provides you with a reference to measure against. This allows for tracking and measuring improvements from FTP, power curve data or more complex fitness elements such as aerobic decoupling when used with a heart rate monitor.

Verdict

Riders who feel they need greater structure in both individual workouts and seasonal plans will benefit from using a power meter. The advantages it provides in terms of data feedback and how that data can be used to maximise training time, pacing for events and recovery management to name a few, makes for a very effective training tool.

ANDY TURNER – SWIFTCARBON PRO CYCLING

I use a power meter for both training and racing. The whole team rides with power on the bikes or Wahoo Kicker smart trainers indoors.

Primarily, I use it to measure actual power, lap power and kilojoules expended. I look at actual power and lap power during an interval session to make sure I stick to the numbers. I also keep an eye on kilojoules to make sure I’m eating enough while doing longer, harder sessions. The rest of the time, I review the data after training.

My training sessions combine perceived effort, FTP percentage, speed, feel and heart rate. Often, I focus on a specific power range, but some days it’s just a free ride with efforts up climbs or TT flats. I look at heart rate to get an idea of fatigue, fitness or possible illness. In an actual race, I just try to go faster than everyone else.

If I could only choose one data output to measure, I would select watts over heart rate. I get a good feeling of what my HR is just by feeling the thumping in my chest.

Good days and bad

On my Wahoo Kickr, I find the power being read towards the cassette, a little lower than the crank-based meter. This is due to losses in drivetrain and other factors, but it’s only a small percentage. Other than that, I’ve set power PBs indoors and outdoors.

There are many times when I’ve aimed for a daily power output but couldn’t sustain it. Some days I struggle to hold threshold power for five minutes. If I’m still recovering after a big block, a tough race or haven’t had much rest, I’ll find some power figures hard to hit and maintain. Other days, I’ll manage 100 more than it during the same duration.

Verdict

Since power meters have become affordable, they’re definitely worth the investment. But don’t get fixated on the numbers. There are so many metrics available nowadays that it can be mind boggling.

A good coach can use your power numbers to ensure your training leads to specific goals. Alternatively, you can read up about it and self-coach. If you’ve started riding for fitness and fun, the most important thing is to get out there and enjoy the ride.

JACK REES – RIBBLE PRO CYCLING

I use a power meter for all racing and training sessions and have one on each bike. It’s the same for every rider on the team. Training methods have developed so much, and riders balance training with education, other commitments or full-time jobs. Power meters provide metrics and allow our riders to maximise each session.

When measuring power, I mainly use a 3s or 5s average to smooth out the numbers a little. For efforts, I measure average power on the lap screen, as well as TSS and IF to follow the session and gauge the demand and intensity.

My training sessions are mainly guided by FTP percentage. I look at outputs during the ride or review them after. It’s always nice to enjoy an endurance or recovery ride without any concern for power, but the numbers guide specific efforts.

Heart rate or watts?

When measuring power, watts beat heart rate every time. 200w is 200w, no matter if that’s into a headwind, up a climb or on the flat. Fatigue, caffeine, temperature and other factors can influence heart rate, but watts always remain constant.

Typically, I find that power indoors can be 10-15% lower than what you’d expect to do on the road. Of course, the data doesn’t tell the whole story. You need to be in touch enough with your body and how you feel alongside the data.

It’s important to remember you’re not a robot. You can’t hit targets day after day. Some days you’ll fall a bit below; some days it just might not happen. It all comes down to your training phase, previous training sessions, when you do the efforts within a session, and so on.

Verdict

If you have performance-based targets, you should be using a power meter to guide your training. On the other hand, they can take a bit of fun and enjoyment away from riding a bike. It all depends on your goals.

My advice is to do some reading and get to grips with how power meters work. Use software that maximises the files and gives you the information in a useable format. Make sure your zones are accurate and that you calibrate your power meter each day.

LAST WORD

You’ve heard it from those who use it. One thing’s for sure: power meters take the guesswork out of your training. If you’re short on time and hoping to improve your fitness and performance by the numbers, they’re one of the best investments you can make.